After Kielce

Summer 1946 – the heyday of the Bricha

Another tipping point occurred on July 4, 1946, after Kielce pogrom, in which 42 Jews were murdered pursuant to a blood libel. The pogrom marked the pinnacle of antisemitic activity in Poland after the Holocaust, which surged after some 150,000 Jews returned from the Soviet Union to Poland during that year under the repatriation agreement. Antisemitic incidents in cities and aboard trains in post-liberation Poland claimed the lives of more than a thousand survivors. As the pogrom in Kielce left the Jewish population terrified, the number of applicants to leave Poland rose and pressure on the Bricha movement mounted. The Government of Poland, deeming itself unable to restrain the antisemitism, considered emigration a way to solve the problem. A secret agreement between the heads of the Bricha and the Polish Ministry of Defense briefly enabled groups to cross into Czechoslovakia via the Silesian border. The emigrants were equipped with a “collective document” that carried an agreed-upon stamp amounting to a “visa” from the Bricha. Concurrently, the Government of Czechoslovakia decided, chiefly under the influence of its Foreign Minister, Jan Masaryk, to open its border to Jewish escapees from Poland. In July–October 1946, more than 70,000 Jews left Poland via Czechoslovakia en route to displaced-prison camps in the American zones in Germany and Austria.

From the inception of the Bvricha until October 1946, more than 180,000 Jews followed the trails of the Bricha. In early 1947, the Government of Poland terminated the border arrangement.

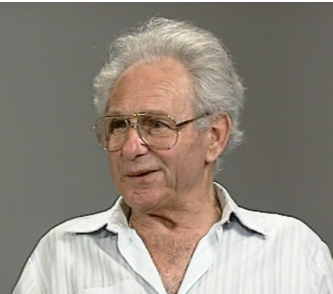

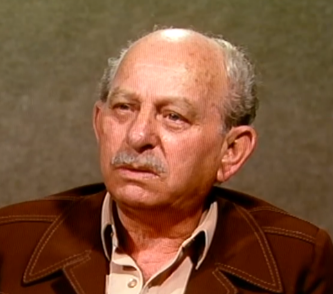

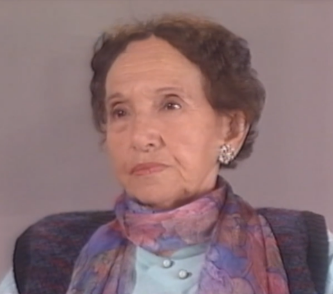

Testimonies

“Terrible antisemitism raged in Poland … and I didn’t care about anything, just to get away”